Kah Bee Chow, Emelie Sandström, Tiril Hasselknippe

For Whom The Bell Tolls

24/03/2022—10/04/2022

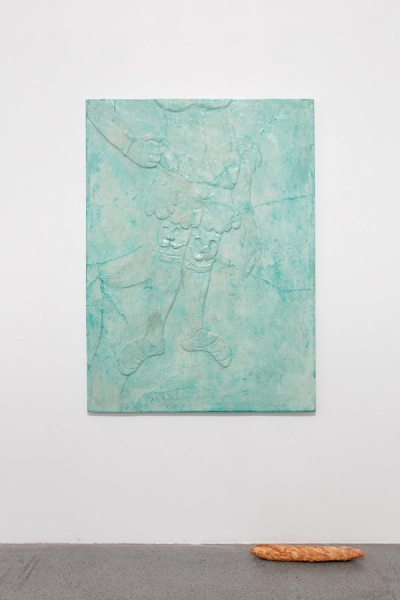

Tiril Hasselknippe, "Centrifuge (all the time forever)", 2022

Recyceled styrofoam, spackelpaste

139 x 70 x 43 cm

Kah bee Chow, "Exhaust-chain or Various Accidents with Sharp Objects", 2022

Steel, scrap metal, latex, muslin, clips, paper, raffia, Hornbach gift wrapping plastic, lurex, thread, washi tape, aluminum, textile

60 cm in diameter x 200 cm.

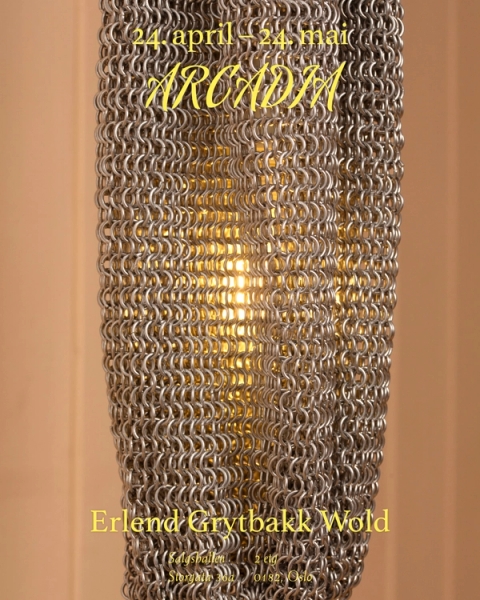

Detail, Kah bee Chow, "Exhaust-chain or Various Accidents with Sharp Objects", 2022

Steel, scrap metal, latex, muslin, clips, paper, raffia, Hornbach gift wrapping plastic, lurex, thread, washi tape, aluminum, textile

60 cm in diameter x 200 cm.

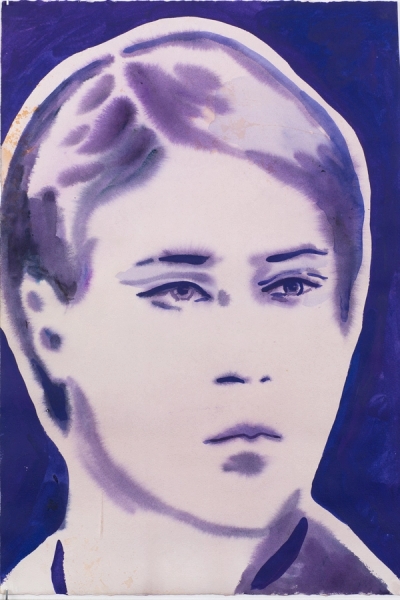

Emelie Sandström, "Cow", 2022

Bronze and ruby

165 x 56 cm

Detail, Emelie Sandström, "Cow", 2022

Bronze and ruby

165 x 56 cm

Rather than having a history, artworks might always have multiple histories. The history of how the work in front of us was created, a story of the artist's choices and actions. Maybe the story of the artist herself and how she relates to her own work. Then a history of reception: the relation between the work and its viewers. Then again, there are also broader stories of connections to other artworks and traditions. Possibly multiple and changing contexts and narratives.

The artwork then, is not completed by the artist. Not entirely. It depends on participation and can be said to have an intermediary nature and relational character. It needs time to be experienced, to settle within its histories.

It could be suggested that the work is somewhere between artist and viewer. That it is a relation. If we follow this line of thought, a work is not the singular creation of the artist, nor the particular experience of the individual.

The foundations of the artists' work, as is the case with every other kind, is never completely their own. Every work participates in a framework within a larger history. Art exists prior to our inauguration of it. To talk about relations in this way, is also to talk about tradition and how tradition shape attitudes. It is to talk about something we share and something that can be shared.

“The creative act is not performed by the artist alone,” Marcel Duchamp writes, and points to the relation with the viewer: “the spectator brings the work in contact with the external world by deciphering and interpreting its inner qualification and thus adds his contribution to the creative act.”

One history of this exhibition is the story of three individual artists, and how these particular works came about. Considering Duchamp as quoted above, we could approach the works as the initial parts of three separate creative acts. Then again, there is another story about how these three artists came to share this room.

A story of artistic development: artists need time to experience, before settling within their own histories. The story of why Emelie, Kah Bee and Tiril share this space, is a story that has to do with art, but also with friendship. They happened to study at the same school at the same time. They share a formative period of study and development.

Often affinities and intimate relationships occur when one artist draws inspiration from another. Through art, friendships can develop across time and space. Ancient works made thousands of years ago seem as fresh as an encounter from this morning.

To return to Duchamp: Though the relation of artist and spectator can seem to be a relation between subjects, that of a creator and a viewer, might there not be openings in artworks to impersonal movements of experience and thought?

We lose ourselves all the time. Sometimes we are given, through this loss, something we did not ask for. This is true of the artist's work too, where the loss of control can lead to new paths in the work. It is not a specific artistic privilege: we lose track of time and place immersed in thoughts, daydreams, books, conversations or intimacy. Could there be something impersonal in these openings of momentary loss? Might not something unknown shine through the artists' actions and choices or the free movements of thought?

We might lose ourselves contemplating old slabs of stone, that polished by time, reflect the colored light from stained glass windows.

Sacred rooms invite us to contemplate loss. A kind of loss that might allow certain impersonal openings. Maybe we pray.

The English poet John Donne contemplated the ultimate loss, as he heard the sound of bells from a nearby church (it was custom at the time, to toll the bells to notify the community of an impending death of one of its congregants). Severely ill and confined to isolation in his bed, he realized that the slow and repetitive ring of the church bells, perhaps signified his own death and not that of someone else.

Later on in his “Meditation XVII” from which the title of the exhibition originates, we find the now proverbial line: “no man is an island”

.Donne's text might be read differently today than when it was written. The universal being in God of the individual, might be understood more along the lines of intersubjective dependency or how we are borne into, and become part of, a preexisting society. At least, it seems, we can say that the poet, confronted with the final loss of self, realized that we are never ultimately isolated.

The creative act is not performed by the artist alone, as Duchamp points out. But artworks depend not only on the company and participation of spectators. Sometimes we act in the company of friends who created works centuries ago. We always think in the company of old ideas. But at other times we might find ourselves in the company of someone we've just met in the school-corridor, and asked to come into our studio on this particular evening, to share their experience of our work with us.

- Stephan Møller